Domia Edwards

Crit 440: Exhibition Histories

December 3, 2019

Project Proposal

I Got A Home in That Rock: Journey to Salvation

Abstract: In this essay, I will propose the project that will culminate in an immersive multimedia exhibition entitled I Got A Home in That Rock: Journey to Salvation. Based on the travels to my mother's hometown of Ardmore, OK, I Got A Home in That Rock uses this town as a backdrop and transforms the white cube into a domestic and spiritual space as a frame. The collapse of exterior and interior spaces allows for an in-depth display of the internality of Black American life where family relations, family history, personal identity, and spirituality intersect with issues of race, politics, and class. I will also examine a series of exhibitions of artists that deal with similar themes and frame the concept of home.

Project Description: Background

Since starting college, I have been creating a series of work as a self analysis to understand who I am, where I come from, and what I believe in. After moving over 4,000 miles away from my home of Atlanta, Ga, I felt disconnected from everything I knew and was searching for something to ground and guide me. I started this journey, questioning my relationship with religion and spirituality, which made me wonder how I was introduced to Christianity and spirituality. I looked at the relationship between my mother and I, her mother, and grandmother. My mother spiritually carried our family in terms of faith. I found this to be consistent with the rest of the women in her family. I was enamored with their strength and resilience and decided to focus my lens on my mother's family and the maternal relationships within it. This step led me to a black hole of discussions about generational trauma, healing, religion, spirituality, ritual, displacement, family dynamics, genealogy, domestic, and spiritual spaces. I learned they needed faith in God because they felt they had to be strong and hold the family together no matter what. I wanted to free them of the burden of containing in their pain by creating a space to talk to each other and be vulnerable. I tried to use my camera to capture the cathartic experience of healing and connecting with my family.

During the process of documenting my family, I put the pieces together. I became interested in the town of Ardmore, OK as the backdrop to my narrative, and its influential role in raising seven generations of my mother's family. My great-great grandfather, a Choctaw Freedman and grandmother, a mixed Chickasaw native, were forced from Georgia to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears. They built their home in Ardmore and that home-raised four generations. My mother referred to Ardmore as a utopia as a child. She never saw poverty in her community. She was taught by and surrounded by Black professionals and successful business owners. Everyone went to college or trade school.

Unfortunately, the Ardmore that exists now is not the same. An opioid epidemic and the War on Drugs hit Ardmore, and black people were disproportionately arrested and sentenced. After integration, tactics like redlining put black communities at a disadvantage. Everyone believes the industrial plant on the train tracks that separate the predominantly black population of the town from the city, has caused illnesses for generations but is ignored. Lack of funding in these communities led to the closing down of quality schools, health facilities, and businesses. Most of my family live in the same houses they grew up in, so they have seen and felt the devastating effects of the changes in the community. Despite these unfortunate realities of the town they once knew to be utopia, my family has always stuck together. My great grandmother had 14 children and 181 grandchildren and counting; we are Ardmore. I have family from all sides of this story from Pastors, business owners, engineers, nurses, teachers, and family that have suffered from disease, addiction, and incarceration.

Project Description: Research

I traveled back and forth to Ardmore, Oklahoma, over the past three years to document the town, my family, the church they built, their homes, and the land they occupied. I conducted academic, practice-based, and field research, to further my understanding of the social, philosophical, and psychological peculiarities of the Black family, specifically mother/daughter relationships. I am particularly interested in the connection between religion and resilience in my family and this community. Simultaneously, investigating how the political and social changes in Oklahoma affected black and native communities. The practice-based research focuses on healing and ending the cycle of trauma through dialogue, conversations, meditations, and therapeutic performances with me and my mothers. The field research consists of photographs, video, journal entries, recorded interviews, and conversations with my family.

Historical / Theoretical Framework

I will further analyze not only how the act of trying to research my own familial history in an attempt to single out my experience to visually recreate it for an audience, but also the content explicitly references so many things that are a part of a long history and "collective" black experience. These things include: having to search for your origins and family line and that search either becoming nearly impossible because of slavery and erasure of people and histories; the attempt to uncover and redraw the history, generational trauma, displacement, the Black church, matriarchal relationships, representation/subjectivity of the Black body in media, visibility, and self-perception. I zoom out my lens to research, not only how my own body relates to these subjects, but also how do these subjects operate on a large scale and throughout history.

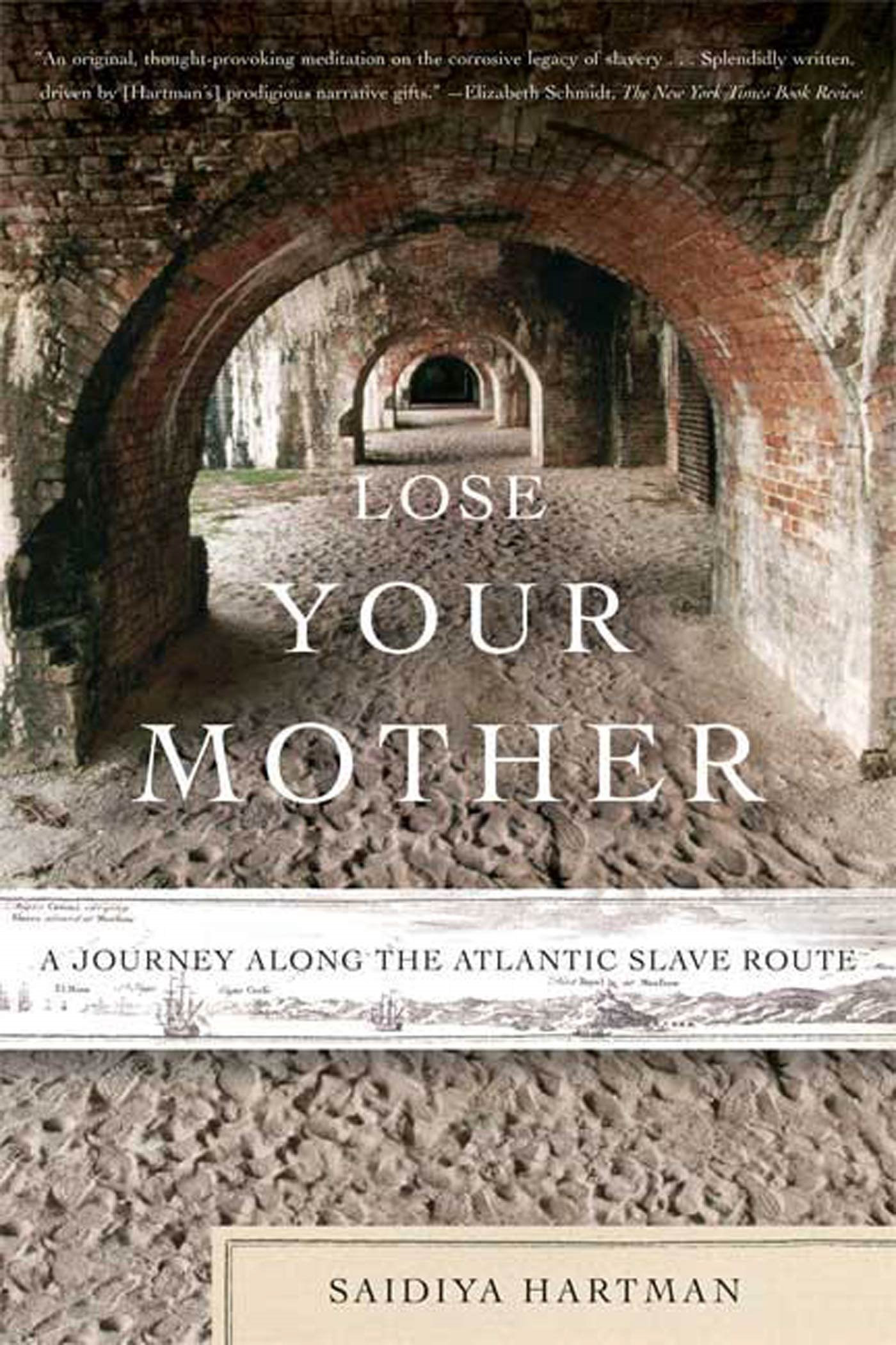

The idea of representation in my work has always been important to me as a Black female artist. Especially with photographing my family, friends, and community that is a part of my experience, that happens to be Black. I want to give them a platform to tell their individual stories and to feel represented. As multifaceted as Black people/experiences are, there is a shared experience on some level. Whether it is your mom blasting old jams or gospel music on Sunday morning to wake you up to clean the kitchen, or the first time you talk about what you are supposed to do if a cop stops you. Harvey Young in his book Embodying Black Experience: Stillness, Critical Memory, and the Black Body address how the "idea of the black body has been and continues to be projected across actual physical bodies: it chronicles how the misrecognition of individuated bodies as "the black body" creates similar experiences". He continues to say that these projections against individuated bodies manifest themselves as acts of violence in various ways such as racial profiling, incarceration, physical and sexual assault. Each of these acts "engenders an experience of the body that informs black critical memory, shapes social behavior or everyday social performances". The trauma endured penetrates black critical memory and seeps into the body that is transferable through generations that informs this experience. Young studies the embodied experience of individuals despite differences in times and geographical locations; they were affected by this projection like Saarjartie Bartmann "Hottentot Venus." She was showcased at carnivals, and even in death, George Curvier dismembered, preserved, and put her body on display at the Paris Museum. Renty, an "African captive," who was photographed as a scientific specimen by Louis Agassiz in 1850. George Ward was attacked by a white mob in 1901. They lynched him and sold his remains as collectors items . These are just a few of the examples that Young lists. As an updated viewer, I would add all the unarmed black people and children being gunned down by police due to this shared projection of a feared black body. The long and violent history of the projection and representation of a black body is always on my mind and the unfortunate reality that they only become apart of history because of these violent acts. We only know them as violated bodies. Their humanity is not included in the canon. Saidiya Hartman, in her essay "Venus in Two Acts," situates the archive as the facilitator of social death in its inability to fully document black lives. "Venus in Two Acts" is about a girl named Venus that dies on a British Slave Ship. Hartman sees the erasure of so many black women from public memory in the history of racial violence within Venus. As a writer, she battles with wanting to fill in the blanks in their stories and wondering if that is her place to do that. I have been asking the same questions as I am starting to find blanks in the archived stories/documentation of my ancestors.

Marshall McLuhan coined the phrase "the medium is the message" in his book Understanding Media: The Extension of Man published in 1964. McLuhan defines a medium as "any extension of ourselves," for example, a new invention, technology, or idea. He also defines message as "the change of scale or pace or pattern" the new invention "introduces into human affairs." It is not the content of the message or use of the innovation, but the changes to interpersonal dynamics a new innovation brings with it that should be the focus of study. McLuhan was concerned with society's focus on the obvious such as the focusing that new technology exists or the information they can access with that technology. We are oblivious to the structural changes to our affairs and perceptions over time. Medium influences society, and society influences medium. The invention of the camera was a huge technological advancement, but at its conception, there was no way to comprehend how powerful and influential it would be. Photography and film allowed us to document our existence, world, tragedies, and triumphs that were the distinct advantage. Once the powers that be understood the power and mass communication of photography, they intentionally used that medium to continue creating propaganda to alter our perception and understanding over time.

I Got A Home in That Rock uses photography, film documentary, sculpture, performance, found objects, written history, and oral histories to capture the interpersonal dynamics within family informed by the history of each of these mediums. The show operates partly as a critique that none of these mediums can fully personify a life or experience, but it can generate a feeling or experience within itself. Self-portraiture and performance is a way that black female artists specifically have reclaimed their bodies and experiences from a history that has violated, objectified, or erased their existence. Conceptual artists Adrian Piper and Carrie Mae Weems have used self-portraiture, archives, performance, text, video, and installation to create spaces for black subjectivity. Lorraine O'Grady's essay "Olympia's Maid Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity" discusses the construction of "femininity" to exclusively associate with the white female form by "assigning the non-white to a chaos safely removed from sight." The black body is rendered invisible as a subject and operates only as an object of otherness. Piper constructs the Mythic Being using stereotypes to achieve hypervisibility as an object of otherness. As "a stereotype that impacts and moves others around him," he is visible to those that saw him in the newspaper, walking on the streets, or in the subway. Through performance Piper allows her objectified body to purposefully take an objective form to access social visibility in order to gain a platform to resist and disrupt the history that positioned black bodies as an object and a commodity. I went to Adrian Piper's retrospective A Concepts and Institutions 1965-2016 at the Hammer Museum in 2018. I appreciated the journey from her early highly conceptual work, to socially confrontational pieces, and ending in these very personal and emotional works that she softens with a touch of comic relief. The socially confrontational section was the most evocative. I have never seen such a blunt display of societal and institutional critique; despite some of this work being 20 years old, the issues addressed are still relevant. Piper creates unfiltered raw one on one confrontations about racism between the work and the viewer, which forces them to question their morality and perceptions.

One of the most moving pieces for me was Black Box/White Box the inside of a black cube displays a quote by Russian writer Alexandr I. Solzhenitsyn from his book First Circle: "Once You have taken everything away from a man, he is no longer in your power. He is free." On the left wall, there is an image of Rodney King's bruised face illuminated by a light box. Opposite the image of King, a picture of George Bush shaking hands with police officers hanging above an armchair a box of tissues and a wastebasket. As the audio from an interview with King ends, the illuminated light box turns off, and the viewer is surprised by the reflection of their own image in the glass illuminated by a spotlight. The White Box is almost identical, but instead of an image of King the video of his brutal beating plays to a looping sample of Marvin Gaye's "What's Going On"--despite the song being about police brutality and injustice the catchy rhythm and melodies sets a jarringly leisurely mood to contemplate or disconnect from the brutal actions happening in front of them. Piper uses such simple gestures to outline how violent acts of racism play out in America. The Black Box embodies the experience of when a black person watching Rodney King, Mike Brown, or Philando Castille be abused and killed by police; we see ourselves and our loved ones. It is our reality. While the White Box creates a passive atmosphere, despite the video of the actual beating plays similar to the videos of all the police killings and they are still unable to connect to the human being that is experiencing that trauma. I thought the creation of these separate environments within the exhibition to hold these emotionally traumatic spaces of mourning, meditation, and critique was crucial to allow the viewer to sit alone with their thoughts and reactions.

Considered to be one of the most influential contemporary artists and one of my biggest influences, Carrie Mae Weems has investigated cultural identity, family relationships, political systems, sexism, class, and representation. She utilizes many strategies such as the archive, photography, and film to create work with black bodies and experiences as the subject. Through performance and self-portraiture in particular, she uses her body to include her presence in landscapes and histories. In her Kitchen Table Series (1990), tells the story of a woman's life through the lens of her kitchen table. The kitchen, the center of domestic life and traditionally the space of the woman in the household, frames her story, showing glimpses of her life and the relationships within it. This project informed the way I reconsidered mundane spaces and objects that we spend most of our lives in and use, and their ability to frame narratives.

Exhibition Description

In my first solo exhibition, I Got A Home in That Rock: Journey to Salvation, my mother's hometown of Ardmore becomes a backdrop, and the white cube is transformed into a domestic and spiritual space to create a frame. The collapse of these exterior and interior spaces allows for an in-depth display of the internality of Black American life where family relations, family history, personal identity, and spirituality intersect with issues of race, politics, and class.

My journey comes full circle by bringing my great grandmother's living room and church into Lindhurst Gallery. When you walk into the gallery it is split in two sides, with dirt covering the floor in between straight ahead there is a confessional structure made out of recycled wood pallets. The room to the left is the chapel and a runner rug makes the aisle between two handmade wooden pews. Two stained glass window light boxes mounted to the walls frame the benches. One of the stained glass boxes depicts a reference to La Pieta with my mother carrying me out of the water. The film entitled "The Land'' is projected on the back wall of the room. There are slow, and still shots of the church intercut with shots driving around the town and still shots of the city. The audio cuts between a sermon and conversations with my family.

The other side is a domestic space. As soon as you cross into this realm, the smell of candles, flowers, and fresh-baked cake consume you. A familiar welcoming living room with a couch and a coffee table. Under the coffee table, there are family albums. The wall facing the sofa is filled with framed photographs of my family and the town, and a tv that sits on a tv stand plays videos of recorded daily interactions with my family from family reunions and holidays. One image, in particular, stands out because the glass frame is cracked. This image is black and white and depicts a fence with a no trespassing sign the wall ends, and provides an opening to see the vacant lot and a large pile of rubble. This picture is of my great-great grandparents' home that was destroyed by the city because it was too old and tried to take the land. My uncle, also known as the Jailhouse lawyer, was finally freed after spending a decade in jail and fought the city to repurchase the property and rebuild the home. Police targeted him for representing black and brown people facing drug charges, and they planted drugs in his car during a stop and continued doing it throughout his ten-year sentence. This image and the broken frame sets the tone for the whole wall of photographs, and story. Despite the loss and trauma, we always hold it together and rebuild it.

On the left side of the space, there is a small dining table where I will have my family's cake. Viewers are invited to sit, have a piece while listening to recorded conversations with the women in my family. On the right side, there is a bookcase and reading chair. The bookcase holds a collection of books that were formative to my upbringing, and informative to the histories displayed in the show.

Holding space was essential to me while conceptualizing this exhibition to give thanks to my ancestors and family and hold space for them in this institution. I knew I did not want to solely take some pictures of my family and the town and throw them up on a wall with a paragraph stating that someone can walk through in 5 minutes and think they get it. I wanted the space to recall where these photographs were taken and contextualize the stories told. I want to utilize every sense of the viewer to transport them to Macedonia Baptist Church on a Sunday morning or my great grandmother's living room couch, and then making them hyper-aware that this is taking place in a gallery setting. I wanted to create a show you have to sit with. Each piece in the show is a part of a whole. The topics that I am discussing in the show are personal, densely layered, and nuanced, but like an accordion can be unjustly simplified or infinitely expanded. It would be impossible to display my whole family history. Through my research and experience with this project, I understand the limitations of the archive and photography capture a life. That is why I wanted to create a feeling or experience and use all different mediums to bring the story to life for the viewers willing to explore the journey.

Exhibition History

The domestic space and the concept of home have been a site of analysis for centuries to understand cultures and civilizations. I wanted to look at how contemporary artists were framing the home through the exhibition. The first exhibition I studied was The Hammer Museum's belonging; an intimate group show that was inspired by the bell hooks novel Belonging: A Culture of Place, a collection of essays that explore notions of home through hooks' journey to and from her hometown in Kentucky. Featuring works by Edgar Arcenaux, Betye Saar, Lorna Simspon, Rodney McMillian, Michael Queenland and Kori Newkirk, belonging explores the interiority of Black American life through the domestic realm. The subtle cultural implications of objects found inside a black home are highlighted in this show. The semi spacious white room allows space for the six works to unfold, and inform each other. Betye Saar's piece Fragments display a photograph of a ripped family photograph, a doily, a feather, a fake bird, a flower, and several other pieces of paper methodically laid out. It recalls the keepsakes you find in your grandmother's house in a box, but contain fragments of information to who the objects belonged to and who are the people in the picture. This piece resonated with me because it displays how black family archives and history are trying to put together a series of fragments to work to complete a picture.

MCA Chicago's 2013 exhibition Homebodies, presents work from contemporary artists that examine the space of home, as an integral site of art production. Featuring work from artists Latoya Ruby Frazier, Adrian Piper, Doug Aitken, Dzine, Barbra Kruger, Do Ho Suh, and many others, Homebodies showcases a wide range of work that incorporate found domestic materials, or represent or recreate domesticity figuratively and literally. Latoya Ruby Frazier's work in the show is apart of her project Notions of Family, where she documents her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania, a former steel mill city. Frazier collapses the spaces of the interior and exterior by documenting the destruction and devastation of her community due to loss of industry, and the mortgage crisis, alongside documenting her family and grandmother as she declines from cancer. Her piece, Home Body Series: Wrapped In Gramps' Blanket, In Grandma Ruby's Velour Bottoms, In Gramps' Pajamas, Covered In Gramps' Blanket, 2010, consists of four black and white self-portraits. In three of the portraits, she stands in what looks like an abandoned home. These photographs have a ghostly presence and recall the abandonment and emptiness it feels to lose someone. Worn clothes hold appearance and memory, similar to the way a home does.